In 1876, Emmeline Wells was called to lead the other sisters of the Relief Society in a grain storage program. The program was both time and resource-intense, with the women required to raise funds for grain, fields and granaries, as well as perform much of the manual labor themselves. During emergencies such as the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, the General Relief Society presidency authorized and coordinated distribution of the grain to those in need. (Embry, J.L.) (Daughters in my Kingdom)

It was a complicated endeavor, made more complicated by frequent attempts by male priesthood leaders to get control of grain program resources for other purposes. In 1883, President John Taylor attempted to put a stop to this behavior with a memo to bishops stating that “the wheat has been collected by members of the [female Relief] Society…and they are the proper custodians thereof…No bishop has any right because of authority as a presiding officer in the ward, to take possession of the grain.” (Embry, J.L.)

This message was reiterated in 1896 by President Wilford Woodruff, who affirmed that even the president of the Church “had no right to take a handful of wheat and dispose of it.” (Embry, J.L.)

But President Lorenzo Snow acknowledged that the problem continued to recur in 1901, when he told the female Relief Society, “You are the only ones among the Saints who are doing anything in a financial way against a day of famine. Your work in this direction is most commendable and I hear as a result that you have 103,783 bushels of grain, together with an amount of flour and beans, safely stored away against a time of need, as well as $3,331 to expend for the same purpose. I understand that in some few instances your labors in this direction have been interfered with but I hope that hereafter there will be no occasion for complaint on that point.” (Deseret Evening News: July 9, 1901)

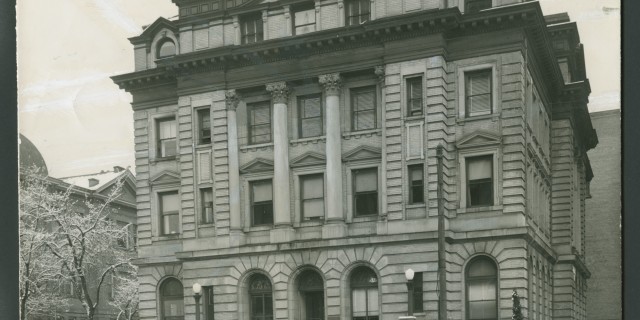

In that same speech, Snow commended the women for another financial endeavor: “I understand that one of the objects of this excursion is to raise funds towards the proposed women’s building in Salt Lake City…that will be suitable as headquarters for the Relief Society, the Young Ladies Mutual Improvement Association, and the Primary Association… I hope to see a handsome structure reared and I anticipate soon having the pleasure of meeting with you in it… You are now 30,000 strong, I am told, with a building fund of nearly $5,000 and with upwards of $100,000 worth of property in your possession.” (Deseret Evening News: July 9, 1901) At the time, the Relief Society raised its own funds and maintained its own real estate. They began fundraising efforts for a headquarters building in 1896 and in 1900, Snow designated a lot for the Relief Society to build on. (history.lds.org) (Parshall, A.E.)

But Snow did not realize his wish to meet with the Relief Society sisters in their new building, nor was he able to fulfill his promise to protect their efforts and resources from male interference. He died only three months after giving this speech. The next president of the church, Joseph F. Smith, envisioned a church in which there would “not be so much necessity for work that is now being done by the auxiliary organizations because it will be done by the regular quorum of the Priesthood.” (Goodman, M.A.) (Teachings of the Presidents of the Church: Joseph F. Smith)

Smith was frustrated by how little priesthood holders were accomplishing, especially in comparison to “the wide and extensive sphere action” undertaken by the female Relief Society. (Daughters in my Kingdom) (Embry, J.L.)

(Goodman, M.A.) This contrast conflicted with his view of the leadership role of males as priesthood holders and the subordinate role of women as non-priesthood holders. As he explained, “Women are responsible for their acts just as much as men are responsible for theirs, although the man, holding the authority of the priesthood, is regarded as the head, as the leader.” (Teachings of the Presidents of the Church: Joseph F. Smith)

In 1908, Smith assigned a new apostle, David O. McKay, to chair a new General Priesthood Committee with the goal of organizing male priesthood holders to do more work. Later, he also asked McKay to chair the church’s first correlation committee, intended to “prevent the unnecessary and undesirable duplication of work in the various auxiliaries of the Church.” (Goodman, M.A.)

In 1909, after the Relief Society had raised most of the money needed to build their headquarters, Smith reversed his predecessor’s decision and reassigned the lot intended for Relief Society to the Presiding Bishopric, requiring the women to donate their building fund to the Presiding Bishopric for a Bishops’ Building instead of the long awaited Women’s Building. The Relief Society was granted use of a few rooms within the new building to meet in but as part of this arrangement, the Presiding Bishopric began supervising Relief Society efforts. (Derr, J.M. & Derr, C.B.) (Parshall, A.E.) (history.lds.org)

In 1918, the government of the United States of America requested to purchase the Relief Society grain storage to address worldwide grain shortages. Without consulting the Relief Society, the First Presidency and the Presiding Bishopric sold the Relief Society’s entire grain supply—the work of four decades—and placed the funds from the sale in an account controlled by the Presiding Bishopric, not the Relief Society. Emmeline Wells, now serving as President of the Relief Society, was understandably upset that Relief Society assets had been sold without her permission. Bishop Nibley apologized but also changed policy; going forward, the Presiding Bishopric would have the final say about the Relief Society’s grain program and the moneys resulting from grain sales. (Embry, J.L.)

In 1923, after Heber J. Grant had replaced Joseph F. Smith as president of the church, McKay’s correlation committee submitted a report with a number of recommendations to better coordinate church programs, all of which were rejected by Grant. He announced a different solution instead: “We wish also to have it clearly understood that all auxiliary associations operate under the direct presidency and supervision of stake and ward priesthood authorities, who carry the ultimate responsibility for the work of these organizations.” (Goodman, M.A.)

This policy solution effectively eliminated the problem of male bishops interfering with female Relief Society efforts, not by stopping the behavior, but by authorizing it. Now that such action was within male bishops’ realm of authority, it could no longer be labeled “interference.”

Amy Brown Lyman became General Relief Society President in 1940, the same year that J. Rueben Clark, first counselor in the General Presidency under Heber J. Grant, began a new push for correlation. Clark had several valid concerns that he hoped to address with correlation efforts: reducing the financial cost of church participation to members—such burdens were a particular problem for women, since Relief Society projects were funded by dues and donations—reducing bishops’ workloads, particularly with regards to overseeing auxiliaries—ironically, such burdensome oversight was mandated by Grant’s 1923 policy—the disparity in church services offered to members in and near Utah compared to those farther away; and preventing debt. These ideas clearly influenced Elder Harold B. Lee, who became involved in correlation a few years later and would eventually lead the church’s most expansive correlation movement. (lds.org) (Goodman, M.A.) (Hall, D.)

These concerns, coupled with Clark’s opinion that women should “not try to be anything else but good mothers and good homemakers,” led to Clark’s conclusions that the Relief Society should abandon its educational, cultural, and social services programs, and instead, focus only on the “promotion of faith and testimony” and supporting the new Church Welfare Plan, which happened to have been created by Clark himself. (Hall, D.)

Lyman resisted. She had founded the Relief Society Social Service Department, served as its head for 16 years, authored much of the Relief Society educational and cultural curricula during her 12 years as Relief Society First Counselor, and had served on the Utah Legislature, so she naturally had a much broader agenda in mind for women and the Relief Society than did Clark. Moreover, she did not believe that women would be willing to join and pay dues to an organization with such a confining mission. (lds.org) (Hall, D.)

But she had no power other than influence, and her influence dried up when her husband, apostle Richard R. Lyman, was excommunicated for adultery. Some blamed Amy Lyman’s busy lifestyle for her husband’s actions, instead of—more logically—the fact that he was raised in a polygamous religion where multiple partners was an anticipated privilege of manhood. Clark asked Lyman to resign the Relief Society presidency and she complied. (Hall, D.)

Lyman was replaced by Belle S. Spafford, who was still in office when David O. McKay became president of the church in 1951. McKay had led the LDS Church’s first correlation committee 43 years previous during the Joseph F. Smith administration. Now that McKay was president of the church, he was still interested in correlation, but this time around, he had authority to implement his own recommendations rather than see them vetoed. McKay assigned Elder Harold B. Lee to lead the correlation effort.

Lee shared many of the goals of his predecessors: coordinating services, avoiding duplication, making the church relevant across cultures and geographies, preventing unnecessary work and activities that would overburden church members, and strengthening the leadership role of male priesthood holders. (Teachings of the Presidents of the Church: Harold B. Lee)

Under Lee’s correlation program, the reporting and financing systems, magazine and lesson materials, and social services once managed by the Relief Society became the responsibility of priesthood leaders and professional departments. Spafford cooperated with these changes, but the termination of Relief Society Magazine, in particular, took place against her will. Lyman’s earlier concern that women would not want to join the Relief Society if it abandoned its projects was nullified by making Relief Society membership automatic to all Mormon women in 1971. (Mulvay-Derr, J. & Cannon, J.R.) (Chandler, G.M.) (Hatch, T.)

As part of this correlation effort, in 1978 the Relief Society transferred the last of its assets to the First Presidency: 266,291 bushels of wheat and nearly 2 million dollars in other assets. In exchange, the Relief Society would at last be funded by tithing dollars, saving women from the expense of paying for Relief Society programs with additional money. Mormon women would also cooperate with male priesthood holders in the holistic work of the church through the newly established council system. (Mulvay-Derr, J. & Cannon, J.R.) (Smith, B.B.)

Today, women may provide input on church finances as they serve on church councils but may not make final decisions. Women are always outnumbered by men as a matter of policy and remain excluded from many councils altogether. Women are barred from most LDS finance-related callings and assignments, such as clerk or auditor. In 2015, the church finally admitted women—or rather, one greatly outnumbered woman—to each of three high-level priesthood councils from which women had previously been barred. However, women are still absent from the Council on the Disposition of the Tithes and the Correlation Executive Committee. This is an important oversight, given the impact of correlation on Mormon women over history.

While some nostalgically wish for a reinstatement of the comparative financial independence the female Relief Society enjoyed in the late 1800s, I believe that a gendered division of administrative responsibilities and financial resources was a failed experiment. It was inefficient and led to conflicts between men and women. Since only men were and are priesthood holders, conflicts were resolved over time by removing female authority and placing financial resources under male jurisdiction.

Correlation was an effort to achieve better coordinated, more efficient church governance, but correlating church auxiliaries under the male-only priesthood resulted in the removal of women from church administrative duties and an increasingly androcentric church. Thus, we now find ourselves living a second failed experiment: patriarchal church governance punctuated by inconsistent efforts to either limit or expand female roles in attempts to access female input without losing male control over financial resources.

Ready for Revelation.

April Young Bennett author of today’s post, is a previous Ordain Women board member and writes for Exponent II.