Last year as my oldest child neared her eighth birthday, my unease grew. That curly-haired girl with her jack-o’-lantern smile wanted to get baptized. But her convert Dad had gone mostly inactive nearly six years ago after becoming concerned about the way the church told its history and over its doctrines concerning polygamy.

I wondered, “Who would baptize her?” Now I knew there would be no shortage of kind, male priesthood holders who would oblige if I asked. But the question wasn’t so simple. Indeed, I knew the real question was, “Who could baptize her without making my husband feel substandard?”

In a church where Dads baptize their kids, when a father doesn’t perform this function it marks them as less than ideal – to the community, to their child, to themselves. My husband felt it was an opportunity to publicly shame him. Thus this event that was supposed to bond parent to child and welcome our child to her religious community became a tense, pressure-cooker.

At one point I remarked, “If only I could baptize her, it would solve everything.” I could see his face and demeanor relax at the idea. Indeed if mothers could baptize their children, it would save us from a lot of the awkwardness of the coming event. And wouldn’t that be a beautiful moment? If a sixteen-year-old boy in my church could baptize her, why shouldn’t I be able to – her mother, a seminary graduate, an Institute graduate & returned missionary.

Of course, I knew a change like that wasn’t happening before my daughter’s baptism. In fact, even worse, the church excommunicated a woman for asking that question too loudly just one week before my daughter’s baptism date.

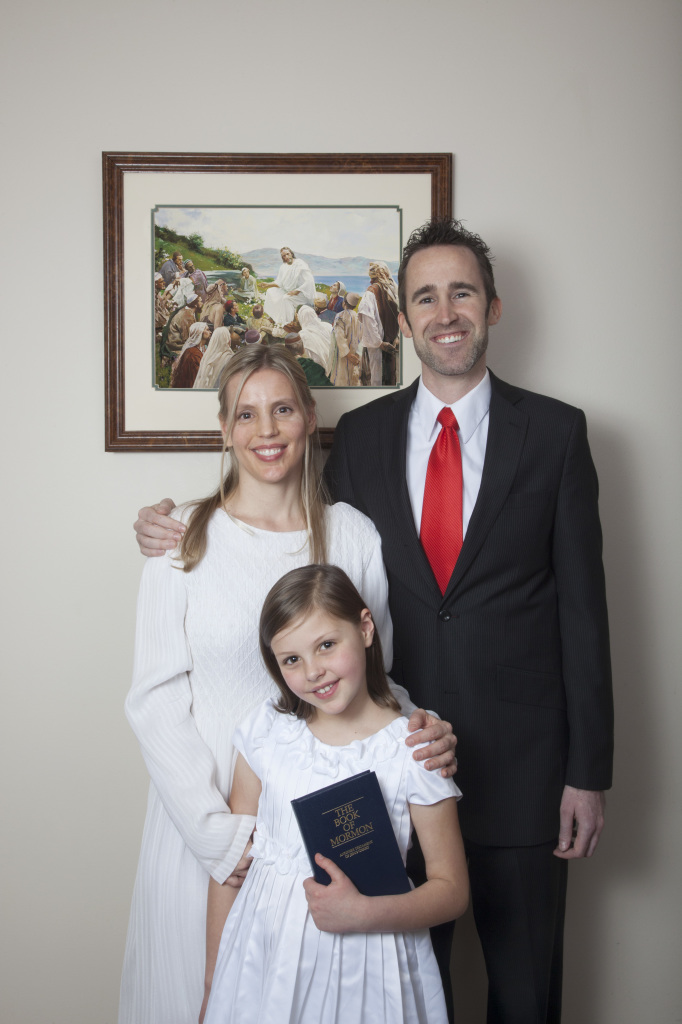

While it was hard to welcome her into a community that didn’t value a diversity of voices, especially female voices, in the end, I decided to make the event as much of my vision of what a religious community should be as I could. And I realized that if I did everything, it wasn’t a community event. The bishop did allow my husband to baptize her. And he set aside his grievances with the church to do it for her. While I couldn’t baptize or confirm her, I could control who would speak, play musical numbers and say prayers by not sharing a baptism service with another family. I chose non-members and like-minded members for these roles. And I had myself give a talk too so that I could tell my daughter everything I would have in a blessing: my feelings, hopes, advice and admiration for her. I shared the things I knew to be true, as if the future of women in the church depended on it (or at least in my small corner of the world). I wanted people to sense that it was a mistake to deny women the full blessings of the priesthood, which include serving in the priesthood and not just receiving blessings and gospel ordinances from priesthood holders. I wanted them to sense that I had lots of power from my Heavenly Father to bless the lives of those around me. I was just waiting for my community to more formally recognize it.

Honoring the past,

Envisioning the future.

Kathleen, the author of this post, has a profile on Ordain Women