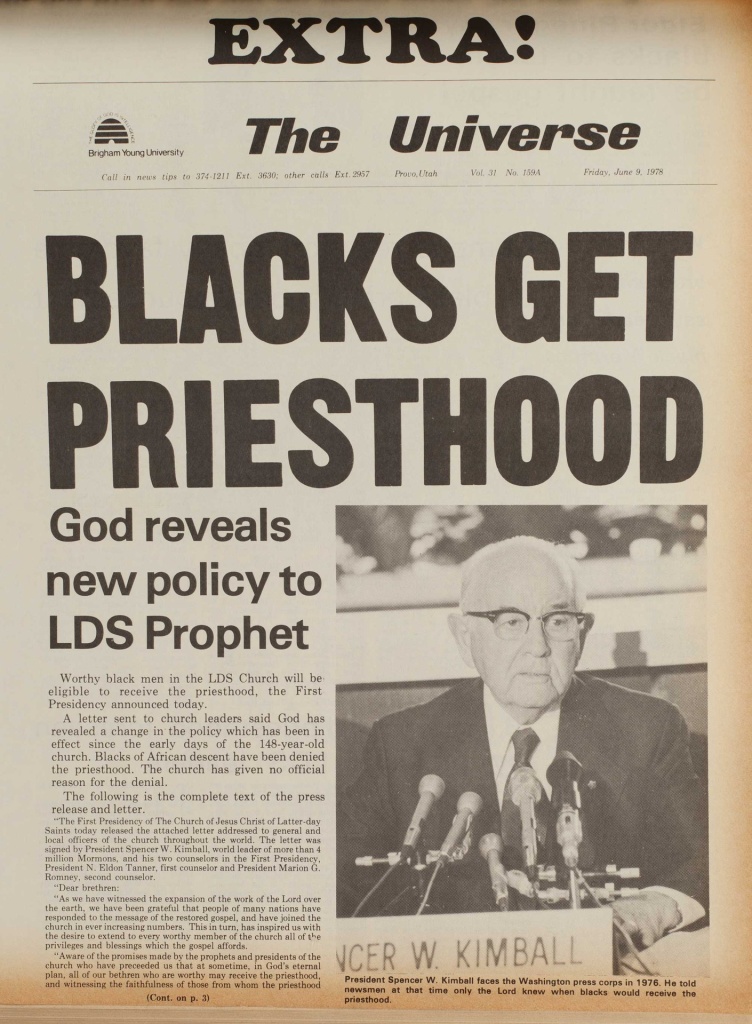

I was in the Language Training Mission (currently MTC) on June 8, 1978 preparing to leave the following week for the Japan Fukuoka Mission. My small group of Japanese-speaking missionaries was in our classroom memorizing the discussions when there was a commotion in the hall. President Kimball had just announced the end to the priesthood-temple ban, which prevented black men from being ordained to the Mormon priesthood and black women from attending the temple and receiving their endowment. Missionaries poured into the halls. Feet lept and hands slapped in high-five celebrations everywhere. It was an amazing moment to be a new Mormon missionary. It was confirmation that in these modern days God was speaking directly to his prophet.

For me, the news came as both an answer to prayer, and a resolution to a difficult internal conflict. While I believed that the gospel was true and that I should serve a mission, I did not know how in good conscience I could teach what seemed to be a bigoted doctrine. More than any other doctrine, the priesthood ban threatened my faith in the church.

My mother, Elva Marchant, was the sixth of fifteen children raised in a small two-bedroom bungalow in the Liberty Ward, just west of Liberty Park in Salt Lake City. Her younger brother Byron Marchant had excelled in tennis as a teenager, after overcoming a serious heart condition as a child. Byron served a mission in France, return and married my Aunt Gladys. They were my “cool” relatives. They were young, good-looking, and socially conscious. They purchased a house in the Liberty Ward, which was located on 500 East, directly across the street from Liberty Park. Byron was employed as the park’s Tennis Pro, and he also worked as the ward’s janitor.

He seemed to be a natural choice to work with the youth, and he was called to serve as the Liberty Ward scoutmaster. In his open and caring way, he not only worked with Mormon boys but also reached out to all scout-aged boys in the area. This included two African-American youth, who turned out to be exceptionally bright, natural leaders. Byron selected these two young men to serve as the senior patrol leader and assistant senior patrol leader for the troop.

While the Boy Scouts of America and the LDS Church are separate organizations, in Utah they are almost one in the same. In 1973, the church initiated a policy, which required that the leadership of a ward sponsored scout troop must be the same as the ward’s deacon quorum presidency. In other words, the president of the deacons quorum must also be the senior patrol leader, and the first counsel must be the assistant senior patrol leader. Because of the discriminatory policy banning black males from the priesthood, Byron was told that he must remove the two African-American youth from troop leadership, and replace them with less qualified white youth. This troubled Byron deeply.

At first, he thought that the policy simply overlooked the unique circumstances of an inner-city ward. He believed once explained, leaders would grant an exception for his unique situation. He misjudged the openness of the leadership. He began climbing the hierarchy to plead his case and was rejected at every level. Rather than understanding, he received condemnation and threats. Meeting with no success, in 1974, he worked with the NAACP, to file suit against the Boy Scouts of America for violating the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The NAACP decided not to file suit against the LDS church, because of the special protections afforded to religions under the First Amendment.

LDS leadership’s refusal to reconsider its policy in light of its discriminatory effect on African-American youth radicalized Byron. He could no longer remain silent about the larger discriminatory policy of the priesthood/temple ban, which had formally been in place since its decree by Brigham Young before the Utah Territorial Legislature on February 5, 1852. Byron began to speak out and to protest.

Byron’s activism split our large extended family in two. My parents, my grandmother and several of my mother’s brothers and sisters supported Byron. My mother used his example to teach me about our troubling Mormon history with race, and the importance of standing up for what is right. Other family members saw anything challenging church authority as evil, and attacked Byron. This split in the family still defines many of our relationships today.

For Byron, the world turned dark. The church fired him as ward janitor. My aunt Gladys was diagnosed and died of brain cancer. Byron’s in-laws, with support from some members of the Marchant family, sued, alleging that he was an unfit parent. But, through it all, he remained true to his conviction that discrimination based on race is wrong, no matter who does it. During these dark days, one afternoon each week, Byron would carry a sign in front of the Church Office Building on North Temple St. in Salt Lake City. I remember driving downtown and seeing him walking in front of the building, all by himself holding his sign. He was determined as ever to do what it right.

Leading up to the October 1977 conference weekend, Byron and a few other like-minded Mormons planned to carry out a protest on Temple Square. By this time, his local leaders were threatening to convene a disciplinary court. After negotiations, Byron agreed to call off the protest in exchange for a promise from his leaders to stop plans to convene a court. The protest was halted, but Byron still wanted to make his point.

I was in my first semester of college that fall, attending the University of Utah. I was also working as a part-time teller at Zions Bank, saving money to go on a mission the next spring. My girlfriend Laura and I planned to spend conference weekend on the couch listening to talks. As we watched the start of the Saturday afternoon session on October 2, 1977, a familiar voice boomed from the television set. I immediately knew it was Byron. “President Tanner did you note my vote?” First Counselor N. Eldon Tanner looked confused, as he searched for the source of the dissenting vote. Security responded by escorting Byron from the building. Byron later explained to the press that his negative vote was meant to highlight the injustice of the priesthood ban.

At 4:00 a.m., Friday, October 14, 1977, the Liberty Stake High Counsel excommunicated Byron Marchant, for his opposition to the priesthood-temple ban. This shocked me because I both wanted to serve a mission, and I also believed the Byron was right. However, despite the LDS church’s very public excommunication of a member for his stand in favor of equality, and against the bigotry of the priesthood ban, less than eight months later, there I was with hundreds of other missionary’s high-fiving and shouting about a new revelation from God. It was a great feeling of relief. But, didn’t God know eight month’s earlier that Byron was right, and that the ban would be lifted?

Thirty-seven years have passed since that day at the Language Training Mission. Nearly all Mormons now believe that racial equality is God’s will. But, for half of the membership of the church, a priesthood ban remains in place. Women are still not allowed to hold the priesthood or participate in church governance. The children of some of the relatives who criticized Byron, occasionally post messages to my Facebook wall criticizing my support for Ordain Women. They say it is wrong to question a church policy. I have seen this movie before. I have faith that right will prevail, and the time will come when today’s critics of female ordination will accept that gender equality is the will of God.

Honoring our past,

Envisioning our future

Mark Barnes, the author of this post, is on the Executive Board of Ordain Women and the Chair of the Male Allies Committee.