Byron’s Song

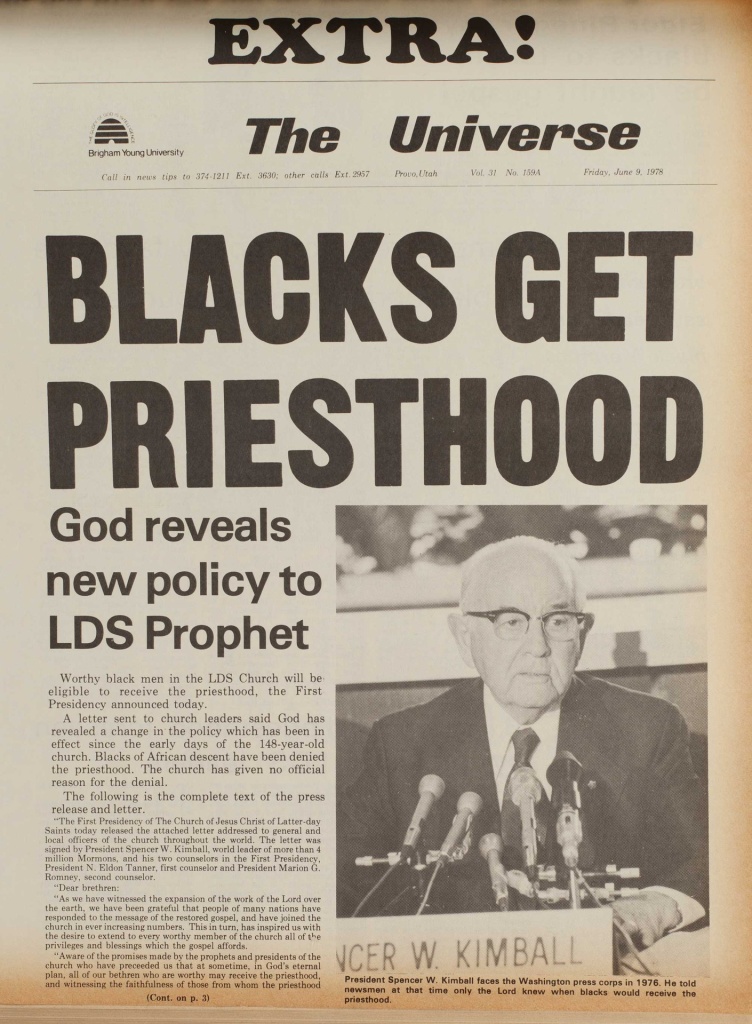

I was in the Language Training Mission (currently MTC) on June 8, 1978 preparing to leave the following week for the Japan Fukuoka Mission. My small group of Japanese-speaking missionaries was in our classroom memorizing the discussions when there was a commotion in the hall. President Kimball had just announced the end to the priesthood-temple ban, which prevented black men from being ordained to the Mormon priesthood and black women from attending the temple and receiving their endowment. Missionaries poured into the halls. Feet lept and hands slapped in high-five celebrations everywhere. It was an amazing moment to be a new Mormon missionary. It was confirmation that in these modern days God was speaking directly to his prophet.

For me, the news came as both an answer to prayer, and a resolution to a difficult internal conflict. While I believed that the gospel was true and that I should serve a mission, I did not know how in good conscience I could teach what seemed to be a bigoted doctrine. More than any other doctrine, the priesthood ban threatened my faith in the church.

My mother, Elva Marchant, was the sixth of fifteen children raised in a small two-bedroom bungalow in the Liberty Ward, just west of Liberty Park in Salt Lake City. Her younger brother Byron Marchant had excelled in tennis as a teenager, after overcoming a serious heart condition as a child. Byron served a mission in France, return and married my Aunt Gladys. They were my “cool” relatives. They were young, good-looking, and socially conscious. They purchased a house in the Liberty Ward, which was located on 500 East, directly across the street from Liberty Park. Byron was employed as the park’s Tennis Pro, and he also worked as the ward’s janitor.

He seemed to be a natural choice to work with the youth, and he was called to serve as the Liberty Ward scoutmaster. In his open and caring way, he not only worked with Mormon boys but also reached out to all scout-aged boys in the area. This included two African-American youth, who turned out to be exceptionally bright, natural leaders. Byron selected these two young men to serve as the senior patrol leader and assistant senior patrol leader for the troop.

While the Boy Scouts of America and the LDS Church are separate organizations, in Utah they are almost one in the same. In 1973, the church initiated a policy, which required that the leadership of a ward sponsored scout troop must be the same as the ward’s deacon quorum presidency. In other words, the president of the deacons quorum must also be the senior patrol leader, and the first counsel must be the assistant senior patrol leader. Because of the discriminatory policy banning black males from the priesthood, Byron was told that he must remove the two African-American youth from troop leadership, and replace them with less qualified white youth. This troubled Byron deeply.

At first, he thought that the policy simply overlooked the unique circumstances of an inner-city ward. He believed once explained, leaders would grant an exception for his unique situation. He misjudged the openness of the leadership. He began climbing the hierarchy to plead his case and was rejected at every level. Rather than understanding, he received condemnation and threats. Meeting with no success, in 1974, he worked with the NAACP, to file suit against the Boy Scouts of America for violating the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The NAACP decided not to file suit against the LDS church, because of the special protections afforded to religions under the First Amendment.

LDS leadership’s refusal to reconsider its policy in light of its discriminatory effect on African-American youth radicalized Byron. He could no longer remain silent about the larger discriminatory policy of the priesthood/temple ban, which had formally been in place since its decree by Brigham Young before the Utah Territorial Legislature on February 5, 1852. Byron began to speak out and to protest.

Byron’s activism split our large extended family in two. My parents, my grandmother and several of my mother’s brothers and sisters supported Byron. My mother used his example to teach me about our troubling Mormon history with race, and the importance of standing up for what is right. Other family members saw anything challenging church authority as evil, and attacked Byron. This split in the family still defines many of our relationships today.

For Byron, the world turned dark. The church fired him as ward janitor. My aunt Gladys was diagnosed and died of brain cancer. Byron’s in-laws, with support from some members of the Marchant family, sued, alleging that he was an unfit parent. But, through it all, he remained true to his conviction that discrimination based on race is wrong, no matter who does it. During these dark days, one afternoon each week, Byron would carry a sign in front of the Church Office Building on North Temple St. in Salt Lake City. I remember driving downtown and seeing him walking in front of the building, all by himself holding his sign. He was determined as ever to do what it right.

Leading up to the October 1977 conference weekend, Byron and a few other like-minded Mormons planned to carry out a protest on Temple Square. By this time, his local leaders were threatening to convene a disciplinary court. After negotiations, Byron agreed to call off the protest in exchange for a promise from his leaders to stop plans to convene a court. The protest was halted, but Byron still wanted to make his point.

I was in my first semester of college that fall, attending the University of Utah. I was also working as a part-time teller at Zions Bank, saving money to go on a mission the next spring. My girlfriend Laura and I planned to spend conference weekend on the couch listening to talks. As we watched the start of the Saturday afternoon session on October 2, 1977, a familiar voice boomed from the television set. I immediately knew it was Byron. “President Tanner did you note my vote?” First Counselor N. Eldon Tanner looked confused, as he searched for the source of the dissenting vote. Security responded by escorting Byron from the building. Byron later explained to the press that his negative vote was meant to highlight the injustice of the priesthood ban.

At 4:00 a.m., Friday, October 14, 1977, the Liberty Stake High Counsel excommunicated Byron Marchant, for his opposition to the priesthood-temple ban. This shocked me because I both wanted to serve a mission, and I also believed the Byron was right. However, despite the LDS church’s very public excommunication of a member for his stand in favor of equality, and against the bigotry of the priesthood ban, less than eight months later, there I was with hundreds of other missionary’s high-fiving and shouting about a new revelation from God. It was a great feeling of relief. But, didn’t God know eight month’s earlier that Byron was right, and that the ban would be lifted?

Thirty-seven years have passed since that day at the Language Training Mission. Nearly all Mormons now believe that racial equality is God’s will. But, for half of the membership of the church, a priesthood ban remains in place. Women are still not allowed to hold the priesthood or participate in church governance. The children of some of the relatives who criticized Byron, occasionally post messages to my Facebook wall criticizing my support for Ordain Women. They say it is wrong to question a church policy. I have seen this movie before. I have faith that right will prevail, and the time will come when today’s critics of female ordination will accept that gender equality is the will of God.

Honoring our past,

Envisioning our future

Mark Barnes, the author of this post, is on the Executive Board of Ordain Women and the Chair of the Male Allies Committee.

Reflections of a Flawed Past- Visions of a Better Future

There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female; [there is neither black, nor brown, nor red, nor yellow, nor white]: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus. Galatians 3:28 (KJV, Edited and enhanced for inclusivity)

. . . and he denieth none that come unto him, black and white, bond and free, male and female; and he remembereth the heathen; and all are alike unto God, both Jew and Gentile. 2 Nephi 26:33

“We all should know that diversity makes for a rich tapestry, and we must understand that all the threads of the tapestry are equal in value no matter what their color.” – Maya Angelou

During the month of January 2015, in keeping with the Ordain Women theme of “honoring our past, envisioning our future,” we created and shared several photographic and videographic images and illustrations. Those images and illustrations depicted how it would have looked it in the past when LDS women were authorized to and did administer blessings and how it could look in the future when we are once again authorized to administer blessings and when we receive authority to perform sacred ordinances.[i]

Like many of you, I have been moved deeply by these images and illustrations of the past. I have read the words strong, brave LDS women used when they washed, anointed, and blessed their sisters and their children and have rejoiced in the strength and power of those words. [ii] I have listened to the reading of the words of a blessing and anointing in preparation for childbirth and have felt the spirit of those women as they administered to their sisters.[iii] I have spent many hours reviewing various publications that recount the history of LDS women administering blessings. I have celebrated that history and I have longed for the spiritual authority held and exercised by LDS women in earlier Church days.

However, as an African American woman, the joy I felt in celebrating the history of LDS women administering blessings has been mixed with a tinge of sadness and perhaps even bitterness–feelings that I vacillated between struggling to subdue and struggling to understand. I kept wondering why this history evoked these feelings in me and why I could not join, completely and wholeheartedly, in the celebration of the history of my sisters.

Somewhere around the middle of the month, a thought began to ring through my head like a clarion call and I realized that my mixed feelings, my ambivalence, and my struggles could all be traced to one simple fact: That history did not include any one who looked like me.

As I continued to think and ponder, the full weight of the situation and my feelings descended upon me. I realized that I could not fully and completely honor the past because the past that was being honored not only did not include women who looked like me, but it specifically excluded women who looked like me. I shed tears of sadness and anger as I thought about how our sisters of African descent–sisters who looked like me–were not allowed to participate in the administering of blessings or to attend the Temple, not because of any divine prohibition, not because they lacked faith, not because they were unworthy, but SOLELY because of the color of their skin. As I shed tears for and drew inspiration from their history, I knew that no attempt to honor our past could be complete without honoring these brave women of African descent, who kept the faith and lovingly served the LDS Church even as the Church relegated them to a status less than second-class membership. These are their stories.[i]

Jane Elizabeth Manning James (September 22, 1822 – April 16, 1908)[i]

Jane Elizabeth Manning James was born on September 22, 1822 in Wilton, Connecticut. She converted to the LDS Church when she was about 16 years old. A year or so after she was baptize, she and several members of her family decided to make the journey to Nauvoo, Illinois, to join other Church members. They travelled the first part of their journey, from Connecticut to Buffalo, New York, without incident. However, when they reached Buffalo, they were not allowed to continue their journey via steamboat even though they had already paid their fares and their bags were already on the boat. They then had no choice but to forfeit the money already paid, leave all their belongings on the boat, and travel by foot for a distance of more than 800 miles. Jane’s description of that long journey is both a heartbreaking account of her struggles and a beautiful tribute to her faith.

We walked until our shoes were worn out, and our feet became sore and cracked open and bled until you could see the whole print of our feet with blood on the ground. We stopped and united in prayer to the Lord; we asked God the Eternal Father to heal our feet. Our prayers were answered and our feet were healed forthwith.

When we arrived at Peoria, Illinois, the authorities threatened to put us in jail to get our free papers. We didn’t know at first what he meant, for we had never been slaves, but he concluded to let us go. So we traveled on until we came to a river, and as there was no bridge, we walked right into the stream. When we got to the middle, the water was up to our necks but we got safely across. Then it became so dark we could hardly see our hands before us, but we could see a light in the distance, so we went toward it. We found it was an old Log Cabin. Here we spent the night. The next day we walked for a considerable distance, and stayed that night in a forest out in the open air.

The frost fell on us so heavy, it was like a light fall of snow. We arose early and started on our way walking through that frost with our bare feet, until the sun rose and melted it away. But we went on our way rejoicing, singing hymns, and thanking God for his infinite goodness and mercy to us–in blessing us as he had, protecting us from all harm, answering our prayers, and healing our feet.

In course of time, we arrived at La Harpe, Illinois–-about thirty miles from Nauvoo. At La Harpe, we came to a place where there was a very sick child. We administered to it, and the child was healed. I found after [that] the elders had before this given it up, as they did not think it could live.

We had now arrived to our destined haven of rest: the beautiful Nauvoo! Here we went through all kinds of hardship, trial and rebuff, but we at last got to Brother Orson Spencer’s. He directed us to the Prophet Joseph Smith’s mansion. When we found it, Sister Emma was standing in the door, and she kindly said, “Come in, come in!”

Jane and her family members then set about building lives for themselves in Nauvoo. When all of Jane’s family members we able to find homes and work except her, she became somewhat discouraged. However, Joseph and Emma Smith offered to let her live with and work for them. Jane’s description of her life with the Smith family reflects that she had a very close relationship with them. The description recounts how Lucy Mack Smith (Joseph’s mother) allowed Jane to handle a “bundle” containing the Urim and Thummin and how Emma asked Jane if she would like to be adopted into the Smith family, a proposal which Jane did not accept at the time.

While living in Nauvoo, Jane met Isaac James, who had relocated from New Jersey. Jane and Isaac were married a few months after the deaths of Joseph and Hyrum Smith. They then joined other Church members on the long trek to Utah. There, Jane and Isaac acquired land and livestock and worked hard to raise and provide for their children. In 1869, however, Isaac made the decision to leave Utah and his family.

Jane remained a faithful, tithe paying member of the Church. In her desire to receive all of the blessings in store for her, including the blessings as exaltation, she repeatedly petitioned the First Presidency and other Church leaders to be endowed and sealed. However, her petitions were not granted.

In 1884 she sent a letter to President John Taylor, and asserted that as a child of Abraham, she should be eligible for exaltation. Jane concluded her letter with the plaintive plea: “Is there no blessing for me?” Despite her plea, her petition was still not granted.

Since her husband was no longer with her, Jane then requested that she and her children be sealed to Walker Lewis, an African American who had been ordained to the priesthood during Joseph Smith’s lifetime. In 1890, she submitted a petition to Apostle Joseph F. Smith in which she wrote:

Dear Brother – – Please excuse me taking the Liberty of Writing to you – but be a Brother by answering my questions – There by satisfying my mind – – First, as Brother James [her husband Isaac] has Left me 21 years – And a Coloured Brother, Brother Lewis wished me to be sealed to Him, He has been dead 35 or 36 years – can i be sealed to him – parley P Pratt or dained Him an Elder. When or how[?] can i ever be sealed to Him.

That petition was not granted.

In 1894, Jane submitted yet another petition to be endowed and sealed. In that petition, she relied upon Emma’s offer to adopt her and asked to be sealed to Joseph Smith, Jr., and his family. President Wilford Woodruff met with her personally to discuss this petition, but it was still not granted. President Woodruff wrote in his journal on October 16, 1894: “Black Jane wanted to know if I would let her have her endowments in the temple [.] This I could not do as it was against the law of God as Cain killed Abel all the seed of Cain would have to wait for redemption until [sic] all the seed that Abel would have had that may come through other men can be redeemed.” (Emphasis added).

In an effort to pacify Jane, the First Presidency “decided she might be adopted into the family of Joseph Smith as a servant, which was done, a special ceremony having been prepared for the purpose.” The ceremony took place on May 18, 1894 at the Salt Lake Temple. Joseph F. Smith acted as proxy for Joseph Smith, and Bathsheba W. Smith acting as proxy for Jane because, as a woman of African descent, Jane was not permitted to enter the temple. In the ceremony, Jane was “attached as a Servitor [servant] for eternity to the prophet Joseph Smith and . . . his family” and “instructed to be obedient to him in all things in the Lord as a faithful Servitor.”

Understandably, Jane, who had been born as a free person, was not satisfied with being sealed to the Smith family as a servant. So, in August 1895, a little more than a year later, she again petitioned to be sealed to the Smiths through the ordinance of adoption. However, she was again denied.

In 1902, Jane again petitioned to be sealed to the Smith family as an adopted family member and not a servant. The minutes of a 1902 meeting of the Council of the Twelve report that “Aunt Jane was not satisfied with this [sealing], and as a mark of her dissatisfaction she applied again after this for sealing blessings, but of course in vain.” That petition was again denied.

Jane’s final petition was made on August 31, 1903, to President Joseph F. Smith. There is no record of the response, if any, to that petition.

No one ever questioned Jane’s faith or her worthiness. Nonetheless, all of her petitions were either denied or left unanswered solely because she was of African descent.

Mary Ann Adams Abel (December 24, 1829 – November 27, 1877)[i]

Very little is known about Mary Ann. On February 16, 1847, she married Elijah Abel, who she met when he relocated in Cincinnati after serving a mission in New York.

Elijah was the first African American to be ordained as an Elder and a Seventy. Elijah, who was a skilled carpenter, worked on the Kirtland and Nauvoo Temples. After Mary Ann and Elijah relocated to Salt Lake, they managed the Farnham Hotel and Elijah used his carpentry skills to help build the Salt Lake Temple.

In 1853, Elijah sought to receive his own endowments. Although no account specifically states that Elijah’s request included Mary Ann, one would presume that it did. Despite the faithfulness of Mary Ann and Elijah and despite the fact that Elijah had helped to build three temples, the request was denied by Brigham Young, solely because of their skin color.

Amanda Leggroan Chambers (January 1, 1844 – March 2, 1925)[i]

Amanda was born a slave in Noxubee County, Mississippi. Although little is known about her early history, she married Samuel Chambers on May 4, 1858; she was his second wife. Samuel had joined the LDS Church as a convert when he was 13 years old, and later had a son, Peter, from his first marriage. Amanda and Samuel remained steadfast in their faith, even though they and their immediate and extended family members were the only LDS members in the area.

After Samuel and Amanda were freed from slavery in 1865, they began saving money so that they could make the journey west to Utah to join other members of the LDS Church. They began their journey in 1870 and arrived in Salt Lake on April 27th of that year. Amanda and Samuel were active members of the LDS church and faithfully paid their tithes; in fact they were reportedly the largest tithe payers in their ward for a long time. Amanda and Samuel also contributed faithfully to the temple fund even though Samuel could not receive the priesthood and neither Amanda nor Samuel was able to enter the temple or partake of any of its blessings. While we can take some comfort in knowing that the ordinance work for Amanda and Samuel was done on April 13, 1984, we must acknowledge the ugly truth that Amanda, a faithful LDS woman, was denied the blessings of that work for almost sixty (60) years.

I have shed many tears and drawn much inspiration from the histories of Jane and Mary Ann and Amanda. I have also shed tears for and drawn inspiration from other African American women, whose faith was just as strong as theirs, but whose stories have not been recorded and who must rely on us to make sure that their names and their stories are discovered and remembered. I promised myself that I would work diligently on this task.

With the names and histories of these faithful African American women running through my head, every fiber of my being compelled me to become integrally and intimately involved in making sure that no blessings of our faith are ever again denied to anyone because of the color of her or his skin. While neither I, as an individual, or Ordain Women, as a group, could do anything to change the historical pictures and accounts, we could make our newly created images of the past reflective of the unifying and uplifting truths expressed in Galatians 3:28 that “[w]e are all one in Christ Jesus” and in 2 Nephi 26:33 that “all are alike unto God.”

With those goals in mind, I eagerly stepped forward to participate in making those newly created images. As I was doing so, I felt transported across time and space and connected with all of my sisters of African descent whose blessings were denied or delayed. I experienced an awe-inspiring vision of what could have been in the past and what can be in the future. I can testify that I have communed with the Spirit and have received personal confirmation that my vision is in keeping with divine will.

There is much work to be done to make amends for the wrongs of our past. However, when I envision our future as LDS women, I envision a future where we recognize and implement and live the basic truth in Maya Angelou’s words that diversity makes for a rich tapestry, and we must understand that all the threads of the tapestry are equal in value no matter what their color.” I know that any effort to bring about gender equality in the LDS Church that does not include every women of every race, color, national origin, or culture will not achieve true equality. Instead it would only be another indignity and another insult to Jane Elizabeth Manning James, Mary Ann Adams Abel, Amanda Leggroan Chambers, and other women of African descent who were denied opportunities to partake of and participate in the blessings and rituals and ordinances of the Church we love.

So, let us honor and celebrate our past. However, let us also openly and honestly acknowledge the mistakes, the hurts, and all the unpleasant truths about that past. Let us repent of and make amends for all of our sins, whether they were of omission or commission. Let us covenant together that we will not make those same mistakes or commit those same sins again. In so doing, we will be able not only to envision but to walk boldly into a future where LDS women reclaim the spiritual authority and power exercised by our sisters in the past, where the daughters of Jane and Mary Ann and Amanda stand on equal footing with the daughters of Eliza and Zina and Patty, and where they ALL have achieved equality in faith with their brothers.

Honoring our past,

Envisioning our future.

[1]With all of the images and illustrations, Ordain Women has acted in compliance with current church policy and no actual ordinances took place in the making of these images and illustrations.

[1]Eliza Snow said “[a]ny and all sisters who honor their holy endowments, not only have the right, but should feel it a duty whenever called upon to administer to our sisters in these ordinances [of healing the sick], which God has graciously committed to His daughters as well as to His sons; and we testify that when administered and received in faith and humility they are accompanied with all mighty power. Inasmuch as God our Father has revealed these sacred ordinances and committed them to His Saints, it is not only our privilege but our imperative duty to apply them for the relief of human suffering.”-Woman’s Exponent, 13 (15 September 1884): 61.

Zina D. H. Young said, ‘’[i]t is the privilege of the sisters, who are faithful in the discharge of their duties, and have received their endowments and blessings in the house of the Lord, to administer to their sisters, and to the little ones, in time of sickness, in meekness and humility, ever being careful to ask in the name of Jesus, and to give God the glory.”-Woman’s Exponent, 17 (15 Aug. 1889): 172.

Patty Bartlett Sessions, who was called by Brigham Young to serve as midwife and who practiced her profession until she was 85 years old, wrote “I felt as though I must lay hands on her. I never felt so before without being called on to do it. She said, ‘Well, do it.’ I knew that I had been ordained to lay hands on the sick and set apart to do that. She had been washed clean and I anointed, gave her some oil to take, and then laid hands on her. I told her she would get well if she would believe and not doubt it.”–Rugh, Susan (1978), “Patty Bartlett Sessions: More than a Midwife”, in Vicky Burgess-Olson, Sister Saints, Brigham Young University Press, pp. 303–322, ISBN 0-8425-1235-7

[1]This transcript was preserved by Oakley Idaho Second Ward Relief Society Minute Book in 1909:

We anoint your back, your spinal column that you might be strong and healthy that no disease fasten upon it, no accident [befall] you, your kidneys that they might be active and healthy and [perform] their proper functions, your bladder that it might be strong and protected from accident, your Hips that your system might relax and give way for the birth of your child . . . . your breasts that your milk may come freely and you need not be afflicted with sore nipples as many are, your heart that it may be comforted. . . . [your baby that it may be] perfect in every joint and limb and muscle, that it might be beautiful to look upon . . . [and] happy and that when [its] full time shall have come that the child shall present right for birth and that the afterbirth shall come at its proper time . . . [that] you need not flow to excess . . .

We anoint . . ., your thighs that they might be healthy and strong that you might be exempt from cramps and from the bursting of veins . . . That you might stand upon the earth [and] go in and out of the Temples of God.

. . . We unitedly lay our hands upon you to seal this washing and anointing wherewith you have been washed and anointed for your safe delivery, for the salvation of you and your child and we ask God to let his special blessings rest upon you, that you might sleep sweet at night, that your dreams might be pleasant and that the good spirit might guard and protect you from every evil influence, spirit, and power that you may go your full time and that every blessing that we have asked God to confer upon you and your offspring may be [literally] fulfilled that all fear and dread may be taken from you and that you might trust in God. All these blessings we unitedly seal upon you in the name of Jesus Christ. Amen. (Emphasis added).

–See, Linda King Newell. “A Gift Given: A Gift Taken: Washing, Anointing and Blessing the Sick Among Mormon Women.” Sunstone Vol. 22 (1999): 30-43.

[1] No one knows how these African American women would have felt about the ordination of women, and I do not include their stories to suggest or imply that they would have supported the ordination of women. Instead, I include their stories because they have been inspirational and instructional to me, as an African American woman and a convert, as I have endeavored to find my place in the Church.

[i] The information concerning Jane Elizabeth Manning James can be found in the following sources:

-“Death Certificate.” State of Utah. April 17, 1908; Jane Elizabeth Manning James. (2014, September 3). Retrieved February 3, 2015 from http://axaem.archives.utah.gov/cgi-bin/indexesresults.cgi?RUNWHAT=IDX20842-IMAGE&KEYPATH=IDX208420016664

-In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 13:56, February 3, 2015, from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Jane_Elizabeth_Manning_James&oldid=623991185, referencing Excerpts from the Weekly Council Meetings of the Quorum of Twelve Apostles, Dealing with the Rights of Negroes in the Church, 1849-1940″. George Albert Smith Papers (University of Utah) and Salt Lake Temple Adoption Record: Book A. May 18, 1894. p. 26.

Smith, Becky Cardon (2005-04-15). “Remembering Jane Manning James”. Meridian Magazine. Retrieved February 3, 2015, from http://web.archive.org/web/20100206222448/http:/meridianmagazine.com/people/050415jane.html.

-O’Donovan, Connell (2006). “The Mormon Priesthood Ban & Elder Q. Walker Lewis: ‘An example for his more whiter brethren to follow’”. John Whitmer Historical Association Journal. (Online reprint with author updates) quoting letter from Jane Elizabeth Manning James to Joseph Fielding Smith, February 7, 1890, LDS Church Archives, transcript in his possession. Retrieved February 3, 2015, from http://people.ucsc.edu/~odonovan/elder_walker_lewis.html

-Mueller, Max (Winter–Spring 2011). “Playing Jane: The history of a pioneer black Mormon woman is alive today”. Harvard Divinity School Bulletin 39 (1 & 2) quoting letter from Jane to President John Taylor. Retrieved February 3, 2015 from http://bulletin.hds.harvard.edu/articles/winterspring2011/playing-jane

-James, Jane E. Manning. Transcribed by Elizabeth J. D. Roundy. “My Life Story”. Wilford Woodruff Papers (Salt Lake City, Utah: Historical Department, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints).

–Newell, Linda King; Avery, Valeen Tippetts (August 1979). “Jane Manning James: Black Saint, 1847 Pioneer”. Ensign (Salt Lake City, Utah: LDS Church). Retrieved on February 3, 2015, from https://www.lds.org/ensign/1979/08/jane-manning-james-black-saint-1847-pioneer?lang=eng

-Young, Margaret Blair. “Jane Manning James: An Independent Mind”. http://www.patheos.com/Mormon/Jane-James-Margaret-Blair-Young-09-10-2012?offset=0&max=1

[i] The information concerning Mary Ann Adams Abel can be found in the following sources:

-Jackson, W. Kesler, Elijah Abel: The Life and Times of a Black Priesthood Holder. (Springville, Utah: CFI, 2013) 72-73.

-Elijah Abel. (2015, January 20). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 15:55, February 3, 2015, from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Elijah_Abel&oldid=643428946

-“Elijah Abel”. http://www.blacklds.org/abel

-“Elijah Abel: Black Mormon Pioneer”. June 8, 2011. 49 Hallelujah Holla Backs! http://sistasinzion.com/2011/06/elijah-abel-black-mormon-pioneer.html

-“Elijah Abel”. http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=9332072

[i] The information on Amanda Leggroan Chambers can be found in the following sources:

-William G. Hartley, “Samuel D. Chambers,” The New Era 4 (June 1974)

-“Samuel and Amanda Chambers: Lesser-Known Pioneers”. http://www.patheos.com/Mormon/Samuel-Amanda-Chambers-Margaret-Blair-Young-10-15-2012?offset=1&max=1

-“Samuel Davidson Chambers”. http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=27442128

-“Tell Me the Stories”. June 8, 2011. 28 Hallelujah Holla Backs! http://sistasinzion.com/2011/07/invisable-pioneers.html

-“Samuel and Amanda Chambers.” http://www.blacklds.org/chambers

An Apology

Ordain Women was invited by our sisters at Feminist Mormon Housewives to share this beautiful and heartfelt message of apology and inclusion. Many of those who support female ordination are our queer sisters and brothers, like these brave supporters and many others

Megan, Brianne, Edward, Michael, Cesar and Justin

I am so sorry for the way LGTBQIA people have been, and continue to be treated by the Church and by some in our community. We can do better and we as an organization commit to being as inclusive as possible going forward and to making the Church a better place for us all.

********

Dear Queer Mormons, We are So So Sorry.

We realize that it is not within our stewardship to apologize for or in behalf of the institution that is The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, however institutions are cold things bogged down in bureaucracy.

Our Mormonism is not cold or distant, it is alive inside each of us, it dwells in our hearts, and informs our choices every day. We love the Gospel. We love our Mormon culture and people. Mormonism is our home, our family. And we know that our queer siblings do not feel the love and belonging that we owe them as a Mormon family.

This last week has felt like a family disaster, like our dear sweet grandpas, from whom we’re used to hearing old-fashioned biased things at family gatherings took one small hopeful step forward, then took a microphone and told the world that the whole family feels the way they feel. We do not agree.

We believe that our queer family deserves a sincere and heart-felt apology. .

We can’t and don’t apologize for the church or our leaders, that is not our place, but on behalf of Our Personal Lived Mormonism, we can apologize.

We are so sorry that you don’t feel safe and welcome at church.

We are so sorry that you have been taught that there is something sinful about who you are.

We are so sorry for the pain and rejection you have felt from your Mormon family.

We are so sorry for all the practices both cultural and institutional that othered you, marginalized you, and made you feel lesser.

And we are so sorry for the times when we didn’t speak up, for the times when we believed these lies too, and for the times when we didn’t reach out and show you the love you deserve.

Dear Queer Mormon family, we want you to know what we believe:

We believe you are worthy of love and belonging.

We believe that you are whole and perfect and exactly as our Heavenly Parents intended you to be.

We believe that our Heavenly Parents want you to experience love and intimacy and have families of your own.

We believe that Church should be a safe haven, where you feel loved and welcomed to come unto Christ.

And we know that these are not the messages that you have received at church.

And for that, we are so so sorry.

Joanna Wallace, is the Social Media Chair on Ordain Women’s Executive Board.

Thank You, Elder Christofferson

We are grateful that yesterday we were able to ask questions live to two apostles, Elder Oaks and Elder Christofferson. The overwhelming response of questions sent to the Tribune demonstrate Church members’ hunger to hear more from those whom we sustain. An active member in good standing asked: “I want to understand whether publicly supporting gay marriage or groups like Ordain Women could cause me to lose my recommend. If I privately believe in these ideas would I still be temple-worthy, and if so, then why would the act of public expression make me unworthy if a privately held belief does not. What is the difference between a belief and its expression?”

Elder Christofferson responded, “We have members in the Church with a variety of different opinions and beliefs and positions on these issues…but…in our view it doesn’t become a problem unless someone is out attacking the church and its leaders, trying to get others to follow them, to draw others away, trying to pull people out of the church, or away from its teachings and doctrines. That’s very different for us, than someone who feels one way or another on a political stance or a particular action to support a group, Affirmation or any others that you named.”

We appreciate Elder Christofferson’s acknowledgement that Church members can have differing positions on issues like women’s ordination. We also are glad that he clarified what constitutes crossing a line: attacking the Church and its leaders by attempting to draw members out of the Church or away from its doctrines. We unequivocally state that Ordain Women seeks to help people remain in the church by providing a safe space to articulate their opinions on gender inequality, about which they previously might have felt alone. In fact, Kate Kelly urged everyone, “Don’t leave. Stay and make things [in the Church] better” in response to the outpouring of grief over her discipline.

We also affirm that Ordain Women teaches no doctrine, let alone false doctrine. All our positions are in line with current Church doctrine and policies: that is, we recognize and comply with the current policy that only men are ordained to priesthood offices. We are simply expressing our heartfelt desire for further light and knowledge through continuing revelation from God. We are grateful that Ally Isom, Church spokesperson, clarified the question on 6/16/14 about where in Mormon doctrine it says that women cannot hold the priesthood when she answered, “It doesn’t.” We also are motivated by the following quote from the Encyclopedia of Mormonism: “Achieving the fulness of the priesthood of the Son of God is the great goal of all faithful Latter-day Saints, because it is the power of God unto salvation and eternal lives.”

Because Mormon women lack institutional authority and access to those leaders who have the ability to receive revelation on behalf of the Church, public advocacy is one of the few options open to us. We desire to work with the Church, not against it, to keep people in the Church, particularly those who feel alone in their desire for women’s ordination through continuing revelation.

Scooping Ice Cream

My friend recently told me about her friend, a woman with twin eight year olds (one boy and one girl). I’m speaking third hand of her experiences, but I think I understand the reason behind her distress clearly.

She’d been troubled after learning the history of our church’s temple and priesthood ban on black members. She thought about how she would have handled such a racist policy. What if she’d had two adopted sons, the same age? What if one has been black, the other white? They both would get baptized together at eight, and they wouldn’t necessarily feel the disparity of their situation at that point. But then she imagined them turning twelve, and ordaining one to the priesthood while the other sat on the sidelines. Every two years, one would be ordained to a new office, passing the Sacrament, preparing and blessing it, collecting fast offerings, home teaching, eventually baptizing and blessing others – based on his personal worthiness – but also based on something he was born with: his white skin.

She really struggled with this idea, and was grateful the ban had been lifted before her time. What a relief that she didn’t ever have to be involved in that practice! There are many painful residual beliefs perpetuating from that time in church history that we are working as a people to still eliminate to this day, but at least the practice has been abandoned and the theories behind it disavowed.

While this mom was actively working to reconcile these historical issues with her faith, it struck her – she did have on her hands a similar situation to that worst case scenario she’d imagined. She had twins, one of which who would be ordained and given responsibility in her ward starting at age twelve, and another who would sit silently on the sidelines while her brother did everything she couldn’t. And it was all because of something he had been born with: his male gender.

I don’t want to imply that my experience as a woman in the church is comparable to that of black members. As a white woman and girl, I was (and am) extended many opportunities and privilege that black members never had. But I have learned from my experience trying to understand the ban on blacks that we often perpetuate things in our church that are based on culture and tradition rather than doctrine or revelation. I think it must always do our duty as church members to question whether we are doing things for a real reason, or if it’s just because of tradition.

Right now, women and girls are not ordained to the priesthood while all men and boys are, almost without exception. Priesthood is required not only to give your sick child a blessing or confirm a new convert to the church, but also to hold all positions of ultimate leadership and authority. At every level of our church, final decisions are made by the male in highest authority, although hopefully they will seek out input from women in the church before doing so.

For me, I struggle to see how women’s issues will be addressed fully until actual women are invited to sit in priesthood leadership meetings and on priesthood only committees (such as those that prepare lesson manuals, direct missionary work, or build temples). However, far before we reach those male only discussions that I long for women to be a part of, there are many things that I believe can easily be recognized as cultural limitations by almost everyone. We can talk about changing those things right now.

For example, my nephew turned 14 not long ago, and his family traveled to Utah to ordain him a teacher among family and friends. Everyone gathered at his uncle and aunt’s house, and the ordination was even postponed almost an hour as a truck driving uncle (who had been traveling all day) came to attend and participate in the circle. It was a great experience. My nephew is a wonderful boy and he deserved the evening in his honor, celebrating his goodness, worthiness and preparation for that moment.

I looked over right after at my niece, his older sister. She was in the kitchen, scooping ice cream for refreshments. She is equally talented, kind and faithful. Where was the fanfare or ritual church experience for her when she moved from Beehives to Mia Maids, or Mia Maids to Laurels?

The fact is, what happens for girls in the church is not the same as what happens for boys. Bishops are encouraged to bring both girls and boys up in front of the congregation during Sacrament Meeting to shake their hand in front of the ward members when they advance in the YM or YW program. But the girls’ recognition always feels so hollow to me. “Congratulations on all your hard work, the bishop has interviewed you and found you worthy to… turn 16.” While the boys are given more public responsibility in the congregation and it makes sense to acknowledge that they are now ordained to say, bless the Sacrament for everyone, calling up the girls feels silly when they’ll still be sitting in the pews, doing nothing. Don’t get me wrong, at the very least we should be acknowledging the girls alongside the boys, but give them something (anything!) to do as well. Maybe they could begin by being sent out as visiting teaching companions the same way the 14 year old boys are home teachers. We could let them share the responsibility of collecting fast offerings or passing the sacrament out to the congregation (neither of which are services that require priesthood ordination, but have just been traditionally only been for boys).

I don’t want to see my daughters always scooping ice cream in the background while we celebrate my son. I love them and want them all to feel equal recognition, love and opportunities to serve in the church. I wish these conversations had been happening in the church when I was a child, but since they weren’t, I choose to stand up and have them now for my daughters. I know we can do better and I want to be part of making those changes.

Honoring our past,

Envisioning our future.

Abby Hansen, the author of this post, is on the Actions Committee of Ordain Women.

Ordain Women Response to Church Press Conference

Sister Neill Marriott, second counselor in the Church’s Young Women general presidency, opened a rare press conference with Church leaders this morning—the first time a female leader has done so. She noted that the push for gay rights was prompted by “centuries of ridicule, persecution and even violence against homosexuals. Ultimately, most of society recognized that such treatment was simply wrong…God is loving and merciful. His heart reaches out to all of his children equally, and he expects us to treat each other with love and fairness.”

Marriott’s observation reminds us of Dr. Martin Luther King’s hope for a more just future: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” As world religious institutions are among the last to end discrimination based on gender and sexual orientation, we have hope that one day universal equality will be reflected in laws, policies and practices everywhere.

Ordain Women applauds initiatives that protect the civil rights and human dignity of all, particularly those who have endured discrimination and marginalization. We trust the cloak of religious freedom will not be used to cover bigotry and prejudice.

#fairness4all #ordainldswomen

Girls can balance trays too

This is a photo-illustration of a 12-year-old Mormon girl passing the sacrament to the congregation. Photo by Daniele Vickers

Honoring our past,

Envisioning our future

On a Sunday when I was ten years old, I went to a different ward than my home ward in Provo, Utah. I was sitting in the back corner of the chapel with my mom and cousin watching a baby blessing. When the young boy brought the white-plastic tray of Grandma Sycamore’s bread, I was far enough away from the next person on the row that I had to stand up between rows of folding chairs. I walked the tray over to the next person who wanted to take a small piece of bread in remembrance of our Savior. For some reason, passing the tray down an aisle of chairs was allowed, but because of my gender, I was not allowed to walk from the front of the church to the back holding bread and water. That was the only time I was ever permitted to hold a sacrament tray for someone else, and it sticks out in my mind even several years later.

The first time I noticed the gender inequality in Mormonism was because of the sacrament. When I was eleven, my best friend was a boy in my Valiant 11 Primary class. However, when he turned twelve in December, something changed in our relationship. Each Sunday, he was given the authority and power to help perform a symbolic atonement. In his white shirt, missionary haircut, and tie, he became a representation of the sacrament. When I turned twelve four months later, I was merely moved to a different Sunday School class. Because my friend—whom I had studied math, played soccer, and watched endless Disney movies with—suddenly was given a new authority that I could never have, our friendship changed. Before I knew about the words for “inequality,” I knew what it could mean in my life. The power to hold a tray symbolized something so much more than walking up and down an aisle.

Now, as a seventeen-year-old, I know the words. My first life experience with inequality and not being able to do something “because I’m a girl” was in my church. I don’t think things should be this way. When I look at my Savior—who is so much more than the represented bread and water we partake of each week—I see someone who showed what true, equal love looks like, and I do not think that His church is where I should have learned about inequality for the first time.

I promise I can balance a tray. As a twelve-year-old, all I wanted to do was go to Young Women’s and talk about Jesus. My childhood faith was unscarred by knowledge of words and the pain of history. And when I walked up and down the small aisle between folding chairs, all I wanted to do was serve. Girls can balance trays too. We can serve in the same ways our male peers can. When it comes to being a servant of our Heavenly Parents, there should be nothing that a girl cannot do.

For My Sons

I was happy to have the opportunity to participate in this photo-illustration for Ordain Women. For me, this photo represents so much of what I love about the LDS church: peace in my faith traditions, joy in Christ’s teachings of love and inclusion, eternal perspective, a stronger sense of my divine nature, and the possibility of further light and knowledge from my Heavenly Parents.

I hope that my sons will remember what this moment felt like, and I hope that the memory will help them think of me as a spiritual leader, capable of having a personal and direct relationship with God. It is because of my faith, and not in spite of it, that I am seeking change with Ordain Women. Ordain Women has given me a place to voice my heartfelt questions, my deepest hurts, and my desires born of faith.

Honoring our past,

Envisioning our future

Cally Stephens, the author of this post, is on the Social Media Committee of Ordain Women.

MLK and Lessons for Gender Inequality

Sean Carter, the author of this post, is in OW leadership. Read his profile here.

“Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be.” — Martin Luther King, Jr.

Dr. King said these words to remind us that we must always be concerned about the condition of the “other.” And not just to satisfy the lofty ideal of equality, but for the very practical reason that we are all inextricably linked in a web of mutuality. As a result, while the shackles of political and economic deprivation were placed directly on the limbs of black Americans during King’s day, they restricted the freedom and prosperity of ALL Americans.

It is this realization that causes me to struggle against the patriarchy that exists today in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. At present, my beloved church restricts the office of the priesthood to worthy males. In doing so, it lessens the power of the priesthood for us all, as we are deprived of the administrative, healing and prophetic gifts of our sisters. And as a result, the work to which we have been ordained is being fettered by the chains of gender inequality.